Setting the scene – Bryn Estyn and North Wales care home allegations; anatomy of a Witch Hunt?

I’m sorry if this is a bit long and dry, but I wanted to put some later comments in a proper context. Here, in outline is the continuing story of North Wales Care Home Abuse scandal.

Beginnings

Bryn Estyn Hall is a large and rather forbidding mansion, which was built in 1904, in the style of an Elizabethan manor house, by a successful Wrexham brewer to replace a previous house. It lies in ample grounds, which earlier formed part of the large Erlas Hall estate on the outskirts of Wrexham. As an approved school, Bryn Estyn remained the responsibility of the Home Office until 1 October 1973, when it became a local authority community home with education on the premises. Responsibility for it passed to the former Denbighshire County Council until 1 April 1974 when the new Clwyd County Council took over. In the mid 1980’s it began to be the centre of allegations being made about abuse of its residents.

This from Wikipedia:

“In the mid-1980s Alison Taylor, a residential care worker and then manager of a children’s home in Gwynedd, began hearing stories from children coming to her home from across Clwyd and Gwynedd about a series of child sexual and abuse incidents in various care homes. On investigation, she found that several reports of these incidents had been made by both care and social workers, but that no procedural or disciplinary action had so far been taken as a result.

Creating a file around cases involving six children, Taylor made a series of allegations against senior social care professionals working for the authority which she raised with her superiors at the council, but again no action was taken. Taylor then reported her allegations to North Wales Police in 1986. The council suspended Taylor in January 1987, alleging that there had been a “breakdown in communications” between Taylor and her colleagues.

On two subsequent occasions, the council offered Taylor a financial termination agreement, subject to her signing a confidentiality agreement. After refusing to sign the confidentiality agreement, Taylor was dismissed. With the help of her trade union, Taylor took the council to an industrial tribunal, which was quickly closed after the parties came to an out of court financial settlement. In September 1989, Taylor accepted the agreement, which did not include an associated confidentiality agreement. In a later Inquiry, Sir Ronald Waterhouse publicly vindicated Taylor. He stated that without Taylor’s campaigning, there would have been no inquiry. Taylor was awarded a Pride of Britain award in 2000, and since 1996 has worked as a novelist.”

In 1991 stories began to be published in the press that Bryn Estyn lay at the hub of a network of a paedophile ring which had worked its way into the care homes of North Wales. Many allegations were levelled, including that senior members of the Police were involved and covering up the abuse, and that shadowy powerful “establishment figures” were involved.

Ultimately, the allegations of child sexual abuse were referred to North Wales Police who undertook an inquiry in 1993, taking some 2,600 witness statements and 300 cases were subsequently sent to the Crown Prosecution Service. As a result, seven people including six residential social workers were prosecuted for abuse, three of whom had worked at Bryn Estyn. One of these was Bryn Estyn’s Deputy Principal, Peter Howarth.

The libel action

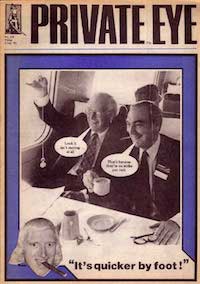

Whilst this was going on, in 1993 serious allegations were made against a senior Police Officer, Superintendent Gordon Anglesea in the press, by amongst, others The Observer, The Independent and Private Eye. At the heart of many of these allegations was the testimony of one Steven Messham, a former resident of the Bryn Estyn the home. Anglesea felt he had no choice and risked all by suing for libel, with a million pounds in costs on the line. The libel trial was heard at the end of 1994, and in the trial Messham’s evidence was taken apart.

Here is a quote from one of the author’s of The Observer’s article, journalist David Rose, given in a speech to a FACT conference in 2013. Rose has undertaken much lauded work in respect of miscarriages of justice as a crime correspondent, including into the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six. He was initially convinced there were real problems at Bryn Estyn. In hindsight, he regrets this. This is what he had to say:

“It became quite apparent when the case went to trial…that Messham was a fantasist; and not only a fantasist but an extremely aggressive and dangerous fantasist who, when challenged would do almost anything rather than confront the reality of his lies….

In fact, what happened during the libel case was that while giving evidence he took an overdose of tranquillisers, collapsed in the witness-box saying it was all too much for him…but to his great credit the Judge insisted that he come back to court the following day when his story further collapsed” [My emphasis]

Messham was later to distinguish himself by physically attacking a QC in the Waterhouse Inquiry referred to below, and more. Anglesea won £350,000 in damages plus costs, and we will return to Steven Messham later on.

The convictions

Here is a list of the convictions which resulted from the police inquiry. I have taken it more or less verbatim from the so-called “Waterhouse Report” entitled “Lost in Care”, ultimately published in 2000 at a cost of £13 million:

(1) 1 July 1993, Mold Crown Court Norman Brade Roberts was convicted of an assault occasioning actual body harm on his foster child. He was acquitted of cruelty to the same child and he received a conditional discharge for a period of two years in respect of the assault. Norman Roberts’ son, Ian Malcolm Roberts received the same order for a common assault on the same foster child. Both offences had been committed between 1980 and 1985. Evelyn May Roberts, Norman’s wife, was acquitted of a charge of cruelty towards the child.

(2) 11 November 1993, Knutsford Crown Court Stephen Roderick Norris, who had been released at the end of his 1990 sentences on 2 February 1993 to a bail hostel at Warrington on various conditions, pleaded guilty to three offences of buggery, one of attempted buggery and three of indecent assault committed between 1980 and 1984 against six boys, each of whom had been resident at Bryn Estyn at the time of the offence. All these offences had occurred when Norris was the Housemaster of Clwyd House at Bryn Estyn. Two other counts of buggery, seven of indecent assault and one of assault occasioning actual bodily harm were ordered to remain on the Court file, as was another indictment alleging six further offences of buggery. All 16 counts left on the file referred to offences alleged to have been committed at Bryn Estyn against other boys in the same period. The total sentence imposed on Norris was 7 years’ imprisonment.

(3) 8 July 1994, Chester Crown Court Peter Norman Howarth, a former Deputy Principal at Bryn Estyn, was convicted of an offence of buggery and seven offences of indecent assault committed between 1974 and 1984 against seven boys who were resident at Bryn Estyn at the time. One of the victims of indecent assault took his own life on 21 May 1995 by hanging himself from a tree. Howarth was acquitted of two other counts of buggery and two of indecent assault involving three other Bryn Estyn residents. He was sentenced to ten years imprisonment in all for the eight offences of which he was convicted but he died of a heart attack in Pinderfield Hospital, to which he had been moved from Wakefield Prison, on 24 April 1997, Paul Bicker Wilson, a former Residential Child Care Officer at Bryn Estyn, was acquitted in the same trial of three alleged offences of indecent assault involving two Bryn Estyn boys, one of which offences was alleged to have been committed jointly with Howarth. Wilson faced a second trial, however, in November 1994.

(4) 28 November 1994, Knutsford Crown Court Paul Bicker Wilson pleaded guilty to three offences of assault occasioning actual bodily harm and one of common assault committed between July 1980 and March 1984 on young male residents at Bryn Estyn, for which he received a total sentence of 15 months’ imprisonment, suspended for two years. A not guilty verdict was entered in respect of another count because the complainant in respect of that alleged common assault in 1984, Y, had committed suicide on 6 January 1994, when he had been found hanging from a door at his home. One other count of assault occasioning actual bodily harm and two alleging cruelty to a child, involving three other Bryn Estyn boys, were ordered to lie on the Court file.

(5) 12 January 1995, Knutsford Crown Court David Gwyn Birch, another former Residential Child Care Officer for six years at Bryn Estyn and subsequently for four years at Chevet Hey, was acquitted of an alleged offence of buggery against a complainant X and of an alleged indecent assault against another boy. X’s evidence against Howarth of indecent assault on him by the latter alone had been accepted by a different jury but had not been accepted by that jury in respect of a joint charge of indecent assault on him by Howarth and Wilson and a separate charge of indecent assault on him by Wilson alone. In the light of the jury’s verdicts in respect of Birch, the prosecution decided not to offer any evidence against him in respect of another count of buggery on X, alleged to have been committed in the same period between 1981 and 1982, four counts of alleged cruelty to children and one of assault occasioning actual bodily harm, two of which involved Y, who had died a year earlier.

(6) 9 February 1995, Chester Crown Court John Ernest Allen, the founder of the Bryn Alyn Community residential schools, was convicted of six offences of indecent assault against six young male residents at the schools between 1972 and 1983. He was acquitted of four other counts of indecent assault involving four different residents. Allen received a total sentence of six years’ imprisonment

It can be seen then that there was one person (Norris) who pleaded guilty to indecency charges, although he maintained a stout defence to some others – that is the reason they were left “on the file”; it was not considered worth while continuing. (Wilson appears to have been overly physical and prone to bullying or thumping the kids). But it does not seem to add up to a paedophile ring on a grand scale – consider the number of staff who must have been employed in these institutions (in the scores if not hundreds) and the number of children (in the hundreds if not more).

However this was not the end of the matter. The problem was that the swirl of rumour that the extent and nature of abuse went beyond these convictions and still hung over North Wales care homes. In particular the rumour that there was an organised paedophile ring operating and abuse by the “rich and powerful.”

In March 1994 Clwyd County Council commissioned a further inquiry, the Jillings Report, undertaken by a panel headed by John Jillings, a former director of social services with Derbyshire County Council.

The Panel were required to “inquire into, consider and report to the County Council upon (1) what went wrong and (2) why did this happen and how this position could have continued undetected for so long” and their attention was specifically directed to such matters as recruitment and selection of staff, management and training, suspension, complaints procedures etc [My emphasis].

However, the remit or style of inquiry appears to have varied. Originally a private internal report, then changed, and then expanded.

Soon after their appointment the panel decided they would advertise for former residents in Clwyd Care Homes to come forward to them.

The panel took some two years to prepare their report. They concluded that abuse had been widespread and they either endorsed, or noted without comment, a number of the more sensational claims. The Jillings Report stated that allegations involving famous names and paedophile rings were beyond its remit, and something best addressed at a potential later public inquiry. It found a child care system in which physical and sexual violence were common, from beatings and bullying, to indecent assault and rape. Children who complained of abuse were not believed, or were punished for making false allegations. The report stated that the number of children who were abused is not clear, but estimates range up to 200; in the early 1990s, around 150 had sought compensation. At least 12 former residents were found to have died from unnatural causes. The report states that some staff linked to abuse may have been allowed to resign or retire early. The report concludes that its panel members had considered quitting before publication, due to: “…the considerable constraints placed upon us.” The final report’s appendices included limited copies of the key witness statements taken by North Wales Police during their earlier investigation.

When their report was completed, however, Clwyd County Council was advised by a leading barrister that its contents were potentially libellous, and might also jeopardise the council’s insurance cover. On 26 March 1996 a collective decision was taken not to publish the report, in spite of the fact that a number of councillors had urged that its publication should go ahead. It is also possible that the members of the panel – or the Council – felt that the report had never been intended or was suitable for public view in any event.

However, the “suppression” or failure to publish the Jillings’ Report fuelled the rumour mill still further – giving rise to the suspicion that there was a cover up of powerful interests, sinister establishment figures and so on.

It was assumed until November 2012 that all publicly held copies of the Jillings Report had been destroyed, and hence it could not be published. In light of the re-emergence of the scandal that month, one of the few legally held remaining copies was sent to the Children’s Commissioner for Wales, Keith Towler.

In November 2012, Anne Clwyd MP called for the legal archive copy of the report to be published, claiming that she was shown a copy in 1994: “I would say please get the Jillings report published because it shows… rape, bestiality, violent assaults and torture, and the effects on those young boys at that time cannot be under-estimated.” BBC Wales subsequently spoke to Jillings about Ms Clwyd’s claim of bestiality, but Jillings said his report did not unearth any such claims. Jillings also commented that public figures were not among names given by victims, and that: “The people the investigation focused on, because these were the people who the children spoke to us about, were staff members.”

However, Jillings commented to other media:

“What we found was horrific and on a significant scale. If the events in children’s homes in North Wales were to be translated into a film, Oliver Twist would seem relatively benign. The scale of what happened, and how it was allowed, are a disgrace, and stain on the history of child care in this country.”

The Waterhouse Inquiry –“Lost in Care”

Not least because of the non publications of the Jillings Report, in 1996, the then Secretary of State for Wales, William Hague, ordered a Tribunal of Inquiry into what were now allegations of hundreds of cases of child abuse in care homes in former county council areas of Clwyd and Gwynedd between 1974 and 1990. Sir Ronald Waterhouse, a retired High Court judge, was appointed to head the inquiry. It may have been that the rumours linking the allegations of organised sexual abuse with repeated allegations of organised abuse by “senior conservative figures” had something to do with this.

The Waterhouse Inquiry was vast. I understand it was originally scheduled to last one year with some months for drafting, but ran for three years from 1997 – 2000.

The Inquiry received evidence of 259 complainants, of whom 129 gave oral testimony in public. The findings of the Waterhouse Inquiry were published in February 2000, as “Lost in Care – Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into the Abuse of Children in Care in the Former County Council Areas of Gwynedd and Clwyd since 1974”

The conclusions are largely set out paragraph 55.10 and following at pages 606 – 608 insofar as most material this piece. The report concluded that:

“(1) Widespread sexual abuse of boys occurred in children’s residential establishments in Clwyd between 1974 and 1990. There were some incidents of sexual abuse of girl residents in these establishments but they were comparatively rare.”

It continued:

(2) The local authority community homes most affected by this abuse were (a) Bryn Estyn, where two senior officers, Peter Norman Howarth and Stephen Roderick Norris, sexually assaulted and buggered many boys persistently over a period of ten years from 1974 in the case of Howarth and about six years from 1978 in the case of Norris and (b) Cartrefle, where Norris continued, as Officer-in Charge, to abuse boys similarly from 1984 until he was arrested in June 1990.

(3)The Tribunal heard all the relevant and admissible evidence known to be available in respect of the allegation that Police Superintendent Gordon Anglesea committed serious sexual misconduct at Bryn Estyn but we were not persuaded by this evidence that the jury’s verdict in his favour on this issue in his libel actions was wrong.

(4) In addition to the abuse referred to in (2) there were other grave incidents of sexual abuse of boy residents by male and female members of the residential care staff between 1973 and 1990 at five local authority homes in Clwyd, namely, Little Acton Assessment Centre), Bersham Hall, Chevet Hey, Cartrefle and Upper Downing.

(5) There was widespread sexual abuse, including buggery, of boy residents in private residential establishments for children in Clwyd throughout the period under review. Sexual abuse of girl residents also occurred to an alarming extent.

(6)The most persistent offender in the Bryn Alyn Community was the original proprietor himself, John Ernest Allen, who was the subject of complaint by 28 former male residents and who was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in February 1995 for indecent assault on six former residents. One other member of the staff was convicted in 1976 of sexual assaults on boys and another was under police investigation for alleged sexual abuse during the Tribunal’s hearings and until his death in August 1998. The Deputy Headteacher of the Community’s school was also convicted in July 1986 of unlawful sexual intercourse with a girl resident under 16 years and sentenced to 6 months’ imprisonment.

(7) Richard Ernest Leake, formerly of Bersham Hall, who was the first Principal of Care Concern’s Ystrad Hall School from 1 July 1974 and later Director of the organisation, is awaiting trial on 8th November 1999 on charges of indecent assault on boys between 1972 and 1978. The Tribunal is aware of 16 male former residents of Ystrad Hall School who have complained of sexual abuse by members of the staff (six have been named). The Deputy Principal, Bryan Davies, was convicted in September 1978 of three offences of indecent assault against two boys and placed on probation. We were unable to hear the evidence in respect of Leake because of the continuing police investigation and the evidence that we heard in respect of other members of the staff was insufficient to justify a finding, except in respect of Davies.

(8) There was persistent sexual abuse, including buggery, of not less than 17 boy residents at Clwyd Hall School between 1970 and 1981 by a houseparent, Noel Ryan, for which he was sentenced in July 1997 to 12 years’ imprisonment. Richard Francis Groome, the former Officer-in-Charge of Tanllwyfan, who was Head of Care and then Principal at Clwyd Hall School between November 1982 and July 1984, has been committed for trial on charges of sexual offences against boys, some of which relate to former boy residents at these establishments. His trial will take place early in 2000.

(9) There was yet again persistent sexual abuse of boy residents of Gatewen Hall, which was a private residential school prior to its sale to the Bryn Alyn Community in 1982. The abusers were the two proprietors from 1977 to 1982, Roger Owen Griffiths and his then wife, now Anthea Beatrice Roberts, who were convicted on 4 and 5 August 1999 in the Crown Court at Chester. Griffiths was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment and Roberts to two years’ imprisonment.

Voluntary homes

(10) There were complaints of sexual abuse from six former boy residents of the only voluntary home that we investigated, namely, Tanllwyfan. They were directed against a former care assistant at the home, Kenneth Scott, who was there from 1974 to 1976 and who was sentenced in February 1986 to eight years’ imprisonment for buggery and other offences against boys committed in Leicestershire between 1982 and 1985. We have no reason to doubt the accuracy of the two complainants who gave evidence of indecent assaults on them by Scott during his period at Tanllwyfan There is one charge against Richard Francis Groome in respect of his period as Officer-in-Charge of Tanllwyfan.

Gwynfa

(11) Allegations of sexual abuse during the period under review at Gwynfa Residential Unit or Clinic, an NHS psychiatric hospital for children, were made by ten former residents to the police and involved four members of the staff. One former member of staff was convicted in March 1997 of two offences of rape of a girl aged 16 years committed in 1991, when she was a resident but not in care. Allegations against another member of staff, Z, were being investigated by the police in the course of the Tribunal’s hearings and some of them were made by former children in care but the decision has now been taken that Z should not be prosecuted. We have not attempted to reach detailed conclusions in relation to Gwynfa for reasons that we explain.

Physical Abuse

(12) Physical abuse in the sense of the unacceptable use of force in disciplining and excessive force in restraining residents occurred at not less than six of the local authority community homes in Clwyd, despite the fact that it was the policy of Clwyd County Council throughout the period under review that no member of staff should inflict corporal punishment on any child or young person in any circumstances. It occurred also at most of the other residential establishments for children that we have examined.

Local authority homes

(13) Such abuse was most oppressive at Bryn Estyn, where Paul Bicker Wilson was the worst offender. There was a climate of violence at the home in which other members of the staff resorted to the use of impermissible force from time to time without being disciplined for it. Bullying of residents by their peers was condoned and even encouraged on occasions as a means of exercising control.

(14) Physical abuse was less prominent in the five other community homes referred to in (12), namely, Little Acton, Bersham Hall, Chevet Hey, Cartrefle and South Meadow, but was sufficiently frequent to affect a significant number of residents adversely. The use of force was often condoned and its effects were aggravated by the fact that some Officers-in-Charge from time to time, such as Peter Bird, Frederick Marshall Jones and Joan Glover, were themselves the perpetrators.

Ysgol Talfryn and Gwynfa

(15)Physical abuse occurred also from time to time at a local authority residential school, Ysgol Talfryn, and at the NHS residential clinic for children, Gwynfa.

Private establishments

(16) Physical abuse was prevalent in the residential schools/homes of the Bryn Alyn Community in its early years and to a lesser extent at Care Concern’s Ystrad Hall School

Abuse in foster homes

(17) There were comparatively few complaints of abuse in foster homes in Clwyd but the evidence before the Tribunal disclosed major sexual abuse in five such homes, in respect of which there were convictions in four of the cases (the fifth offender hanged himself before his trial).

The Report concluded:

“The evidence before us has disclosed that for many children who were consigned to Bryn Estyn, in the 10 or so years of its existence as a community home, it was a form of purgatory or worse from which they emerged more damaged than when they had entered and for whom the future had become even more bleak.”

The report found no evidence “to establish that there was a wide-ranging conspiracy involving prominent persons and others with the objective of sexual activity with children in care”, but did recognise the existence of a paedophile ring in the Wrexham and Chester area.

The public version of the report named and criticised almost 200 people, for either abusing children or failing to offer them sufficient protection. Although it identified 28 alleged perpetrators, many names were redacted due to either pending prosecutions or lack of evidence.

By the way, it was before the Waterhouse Inquiry that Steven Messham gave evidence which involved attacking a QC when confronted about his evidence. Documents proved some of Messham’s evidence to the inquiry to be false. Although Sir Ronald Waterhouse concluded that Messham had experienced abuse, he described him as ‘an unreliable witness’ who was unlikely to be trusted by any jury – a conclusion also reached by the Crown Prosecution Service.

According to my Wikipedia source, the Report led to settlement of 140 claims for compensation based on child abuse. But matters did not end there.

Operation Pallial

On 2 November 2012, following the revelations in the Jimmy Savile sexual abuse scandal, the BBC current affairs programme Newsnight aired an item about the “scandal” in which one of those who had suffered abuse in care homes in North Wales in the 1980s made further allegations that there had been a much wider circle of abusers, including businessmen, members of the police and senior politicians, extending beyond the immediate area to London and beyond. The victim said he had been taken in a car to the Crest hotel in Wrexham and abused more than a dozen times by what Newsnight termed “a prominent Thatcher-era Tory figure“. He called for a further investigation to be carried out.

This resulted in the allegations which swirled around the internet about Lord McAlpine. These were proved to be absolutely untrue, and the whole matter proved shattering for Newsnight, the BBC and the hapless Director General of the BBC George Entwistle was duly forced to fall on his sword in an (albeit lucrative) act of Hari-Kiri. The “victim” himself was forced to offer an unreserved apology to Lord McAlpine.

Nevertheless, such was the panic before all this became clear, by 6th November what has become known as Operation Pallial had been initiated, as well as a judicial investigation into the original Waterhouse Report and whether it had been too narrow in its terms, the Macur Review.

I take the gist of the following from Wikipedia:

The report of Phase One of Operation Pallial was published on 29 April 2013. It set out a total of 140 allegations of abuse, involving girls and boys between the ages of 7 and 19, at 18 children’s homes in north Wales between 1963 and 1992. During the inquiry, 76 new complainants came forward, and the police reported allegations against 84 individuals, of whom 16 had been named by more than one complainant. Some of those named were deceased. The Chief Constable of North Wales, Mark Polin, said: “Offenders quite rightly should have to look over their shoulders for the rest of their lives.”

In November 2013, the police stated that, since November 2012, 235 people had contacted them with information about alleged abuse in care homes in north Wales. Detective Superintendent Mulcahey said that over 100 names of alleged offenders had been put forward to Operation Pallial, and said that the police were “currently pursuing a large number of active lines of enquiry”. A fifteenth arrest, of a 62-year-old man from Mold, was reported on 20 November. Further arrests, bringing the total to 18, were reported on 12 December. Indeed, one of the persons who has since been arrested is none other than former Superintendent Anglesea.

And the trigger for Operation Pallial, the complainant to Newsnight, was none other than…Steven Messham, who’s reliability has already been discarded by the Waterhouse Inquiry. In fact, this is what the Waterhouse Inquiry actually had to say about Steven Messham who was referred to in the report as witness “B”:

“9.33 One of these matters, which inevitably leads to prolonged cross-examination, is the sequence in which his complaints of abuse have emerged. It is not unusual for a complainant of sexual abuse or a child complainant generally to deny at first that any abuse has occurred but in B’s case we have had before us a plethora of statements. These included eight main statements made to the police between 30 March 1992 and 8 February 1993 but B alleges that the police have failed to produce six other statements that he made to them. Rightly or wrongly, he complains also of insensitive behaviour, and in some cases, downright misconduct on the part of a small number of officers involved in interviewing him. In view of the potential difficulties, B was permitted exceptionally to draft his own statement to the Tribunal rather than be interviewed by a member of the Tribunal’s team. The statement runs to 48 pages, in the course of which B alleges that he has been sexually abused by 32 persons (eight of whom are not named) and otherwise physically abused by 22. It is not surprising in the circumstances that B’s recollection, in a limited number of instances, was shown by contemporary documents to be incorrect.

9.34 In the light of these and similar difficulties it was decided in March 1993 by the Crown Prosecution Service, in consultation with counsel, that reliance ought not to be placed on the evidence of witness B”

And here is a rather interesting article on Mr. Messham published by the Daily Mail.

Now it is true that recent investigations have resulted in convictions which seem to me to be sound and just, and I suspect they will do so again in the future. However, the clear concern is that they have moved into a realm in which the culture of investigation has become one in which there is a real risk of fostering unjustified allegations and resulting in unsafe convictions of care workers, teachers and the like, arising particularly in terms of a culture which trawls for accusers, and in which the truth of the accusations and the guilt of the accused is being consciously or subconsciously assumed.

The practice of “trawling” for evidence – inviting complainants to come forward – and the cross-fertilization of accusations by clumsy and credulous investigation techniques are also to the fore. There is also the driving force of claims for compensation. I will analyse these in another piece dealing with the North Wales sage.

To be continued.

©Gildas the Monk

100 Years ago, the daily circulation of The Times was around 5,000. Today it is nearer the 400,000 mark.

100 Years ago, the daily circulation of The Times was around 5,000. Today it is nearer the 400,000 mark. It was The Times who sent William Russell out to share the Crimean trenches with the young men who gave their lives for us. He was described by one soldier as ‘a vulgar low Irishman, [who] sings a good song, drinks anyone’s brandy and water and smokes as many cigars as a Jolly Good Fellow. He is just the sort of chap to get information, particularly out of youngsters.’ Quite so. The perfect ‘reporter’. Without William Russell we would never have known of Florence Nightingale, nor the true horrors of war.

It was The Times who sent William Russell out to share the Crimean trenches with the young men who gave their lives for us. He was described by one soldier as ‘a vulgar low Irishman, [who] sings a good song, drinks anyone’s brandy and water and smokes as many cigars as a Jolly Good Fellow. He is just the sort of chap to get information, particularly out of youngsters.’ Quite so. The perfect ‘reporter’. Without William Russell we would never have known of Florence Nightingale, nor the true horrors of war.